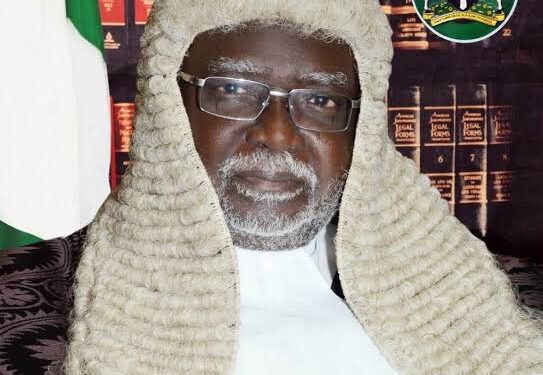

On August 22, 2024, Olukayode Ariwoola, the penultimate Chief Justice of Nigeria (CJN), retired from the bench and became a published author. At a well-attended event in Abuja, the former CJN beamed at the public presentation of his autobiography. Published under the title Judging with Justice*, the book was ghostwritten by Olanrewaju Akinsola (the author better known as Onigegewura).

Laid out in 13 chapters and 496 pages, the author tells his story in the first 250 pages. The remainder of the book is dedicated to testimonials from the author’s colleagues in the judiciary, lawyers, friends, peers, and family members.

The story reveals the son of a doting and committed dad who appears to take family and his faith seriously. Judging with Justice is a deeply personal story about a judicial figure whose rise to the highest office in his country’s judicial grease pole was as improbable as his unusual route. The author is quite open about his health, including open-heart surgery in London in 2016.

Olukayode Ariwoola became a lawyer at 27 and a judge at 38. In the eleven years between his enrollment at the bar and his elevation to the bench, He worked first as state counsel in Oyo State, after which he resigned to private legal practice. That stint of his professional career began in Ibadan, the state capital, under the tutelage of Ladosu Ladapo, a Senior Advocate of Nigeria (SAN) who twice ran unsuccessfully for the presidency of the Nigerian Bar Association (NBA).

After one year of practice under the senior advocate, Olukayode Ariwoola set up his legal practice in Oyo, not far from his beloved natal community of Iseyin. At the time, there were only five lawyers in the city. Making ends meet was difficult, and his clients were mostly reluctant litigants, many of whom had to improvise to find the currency for transacting business with a lawyer. He stuck with it and in 1992, the year after Oyo State was split in two to produce Osun State, got propelled to the office of a judge of the High Court of Oyo State by what, from his narration, was a stroke of providential happenstance. In the cohort of six new judges, Olukayode Ariwoola was the youngest by all of nine years.

After 13 years as a high court judge, Olukayode Ariwooola was elevated to the Court of Appeal in November 2005. The major actors in his elevation to the appellate bench included Aloma Mukhtar, who later became Nigeria’s first female Chief Justice; Bola Ige, a former Attorney-General of the Federation; and Bolarinwa Babalakin, a former Supreme Court justice. None of these three shared the same origins with Olukayode Ariwoola. Aloma Mukhtar came from Kano; Bola Ige and Bolarinwa Babalakin came from Osun State.

After six years on the Court of Appeal, Ariwoola ascended to the Supreme Court in November 2011, where he served for another 12 years before becoming the CJN. His judicial career spanned nearly 32 years, including two years and two months served as CJN. All his judicial elevations (except his preference for the office of CJN) occurred in November.

Judicial autobiographies, especially in common law countries, are far from easy to confection. The balance between achieving a captivating narrative and preserving the mystique of the high judicial office is hard. The temptation to deodorize the tale can be tantalising. Judging with Justice wrestles valiantly with this dilemma and not always successfully.

The author offers that the Supreme Court is “more than a court of law. It is the tradition that the Supreme Court is regarded as a court of policy.” Having said this, the book offers no insight into how the Supreme Court on which he sat for 13 years or the office of the CJN, which he occupied for over two of those years, articulated or advanced this idea of the Supreme Court as a court of policy. If anything, the court did the opposite under him.

The best that can be said of the book and its author is that they chose to be economical with any indication of a coherent judicial philosophy. Entirely in keeping with this, the author writes with what appears to be some pride that he never “had any cause to write a dissenting opinion, be it at the Court of Appeal or the Supreme Court.” He spent a combined 18 years in both courts.

The author, nevertheless, drops hints of inspiration. He counsels, for instance, that “a judge must not frequent social events where litigants and lawyers congregate.” Those who read this may wonder whether he remembered it when he showed up in Port Harcourt in November 2022 to serenade politicians (many of whom had cases before his court) in their quest for electoral victory in elections that were then impending.

Many who were witness to Olukayode Ariwoola’s tenure as CJN will wonder when he came to what he claims in the book to be his long-held belief “that the judiciary is an independent and separate arm of government and should not be regarded as an appendage of the Executive or the Legislature”. The disposition of his entire term appears to have been the very opposite of these sentiments.

Judging with Justice is littered with a few more examples of warm and comforting shibboleths. Yet, it is what the book omits that is most telling.

The author thanks “God for the privilege to have been instrumental in appointing people into positions of responsibility”. As CJN, he sure had a lot of practice at this. He also claims that he always “ensure(d) that the persons to be nominated are credible, qualified, and people of proven integrity.” His record as CJN will show this claim to be worse than bogus.

At the end of his narration, the author takes pride in his achievements as CJN. Among these, he lists attainment at the beginning of 2024 for the first time in the 70-year history of the Supreme Court of full judicial establishment size of 22 (including the CJN). He also points to the appointment since 2023 of new judges to the various courts, including the Court of Appeal, the Federal High Court and the High Court of the Federal Capital Territory.

In Judging with Justice, Olukayode Ariwoola is punctilious in listing all the people he processed for appointment in that frantic sequence of judicial elevations that occurred the year preceding his retirement as CJN. He takes fulsome paternal pride in the fact that his son – also named Kayode Taslim – “is a jurist like Judge Taslim Olawale Elias he was named after” but omits to disclose that it was him, the father, who appointed the son to the role of judge (with no need for the helping hand of a Holy Ghost).

He did not stop there; he also appointed his daughter-in-law as judge, as well as the daughters of the President of the Court of Appeal, the Chief Judge of High Court of the FCT, the daughter of his predecessor in the office of CJN, the wife of the Minister of the FCT; and many more high-up insiders too numerous to mention.

Judging with Justice missed an opportunity to show how a judiciary of sons, daughters, wives and even a few mistresses meets the standard of “credible, qualified, and people of proven integrity.” He may have been closer to the mark if he had titled the book “A Convenient Memory.”

A lawyer and a teacher, Odinkalu can be reached at chidi.odinkalu@tufts.edu

Olukayode Ariwoola, Judging with Justice: The Autobiography of Hon. Justice Olukayode Ariwoola, GCON, The Chief Justice of Nigeria [As Narrated to Olanrewaju Akinsola, (Onigegewura)], (Lagos, Asco Publishers, 2024)