A few days ago, a post about the Anambra State Government House under construction appeared on my timeline. The cost of the governor’s official residence, estimated at over N6 billion, immediately made my mind race to Ayi Kwei Armah’s seminal work, The Beautiful Ones Are Not Yet Born.

The race wasn’t so much about mentally recapitulating the metaphors Armah deployed to highlight the wastes that underline postcolonial governance as it was about understanding wasteful governance as a betrayal of citizens who hope for a meaningful life but find themselves trapped in multidimensional poverty while rulers build grand palaces as government houses.

Does building stately mansions and grand palaces by these political leaders, amid crumbling public infrastructures, who should be more circumspect in spending scarce state resources on projects that bring no real value to the lives of those they govern, not prove Armah’s suggestion right that true change requires the beautiful ones—a generation of committed, compassionate and ethical leaders who are yet to be born?

Anambra State is not alone in the madness of erecting edifices of opulence. The madness, which manifests as nothing more than a sickness, to borrow from Michel Foucault, points at the abnormality that had seized the mind of Abuja even before it seized Anambra State and elsewhere. Just last year, Nyesom Wike officially opened the palatial official residence of the vice president to the consternation of citizens who considered the N22 billion spent on constructing the residence extravagant.

In a country where citizens’ hope for a secure future is constantly interrogated by the struggles for survival, spending scarce state resources on building official residences of grandeur, similar only to Mobutu Sese Seko’s grandiloquent palace now hiding under the umbrellas of tall trees of the deep tropical rainforest of Gbadolite, DR Congo, not only symbolises extravagance but also signposts tragic governance failures. These Gbadolite-like structures raise serious questions about our rulers’ public service ethos.

Mobutu’s personal Xanadu, famously described by David Smith of the Guardian of London as the African Versailles, sprawls first as a built monument to the memory of a maximum ruler who lived his dreams by splurging state resources on his comfort and at the expense of his country’s men, women, and children, and latterly as a vegetative ruin that depicts the transience of power.

Here, governors appear to be reliving Mobutu’s greed by erecting their Versailles in the conurbations of States’ capitals with taxpayer money while ordinary citizens, laden with heavy yoke, scrape the bottom barrel of poverty. Taraba State, for instance, spent over Fourteen Billion Naira (N14b) in 2015 on its new Government House despite the prevalence of intense multidimensional poverty in the state.

Similarly, Zamfara State, with a local debt burden of over N112.2 billion and 78 per cent of its population poor, spent N11 billion under Abdulaziz Yari to build a Government House. Osun State, under former Governor Rauf Aregbesola, built a new Government House while the state struggled with huge debts and unpaid workers’ salaries. Also, former Governor Mohammed Abubakar embarked on an expensive Government House project in Bauchi State, ignoring the state’s overstretched resources.

For many governors, who have become our modern-day dandies, these government house projects aren’t about governance as they are more about their obnoxious attachments to leaving “legacies” of grandeur behind when they complete their constitutional tenures. These attachments reveal a deeper and more troubling attachment to the grotesque Mobutu Complex that at once highlights vulgar ostentation and misuse of state resources.

Governance for them isn’t about public service; it is more about self-aggrandisement and perhaps the hideous kickbacks that invariably inflate construction costs and fatten private accounts.

As with supporters who justified the N6 billion Anambra State Government House, with “gatehouses, police posts, perimeter fence measuring 2.22 linear kilometres and other internal works such as driveways, parking areas, walkways, drainages, water supplies, green area, etc”, on my Twitter timeline, there are those who claim that the government houses would attract foreign investments. Hear: no investors prioritise the aesthetics of government houses over infrastructure or vanity projects over a governance environment that makes the ease of business possible. None.

The human cost of these projects is immense. The billions spent on these opulent mansions could have been invested in human development, for instance, or used to address the insecurity plaguing these states. Rather, our dandies, retreating to the fortresses of government houses, prefer optics to substance and their safety to the safety of the governed.

Good luck to ordinary citizens who sit like ducks in their unfortified neighbourhoods until itinerant bandits and insurgents snatch them. Last week, five members of a family were kidnapped from their home in an Abuja suburb. The remains of the mother of the house were eventually recovered from a forest in nearby Niger State, with the whereabouts of others still unknown.

Building opulent government houses reflects a governance model only fit for the monarchy- not a constitutional democracy. Governance in a constitutional democracy is driven by service to the people rather than self-aggrandisement. Governors must learn two things as our country continues to confront its numerous challenges.

First, beautiful buildings don’t make a good government. Second, leadership is about delivering on projects that improve citizens’ lives. The era of vulgar ostentation must end, and scarce resources must be channelled into building a country that works for all citizens. Only then can our country begin to fulfil its immense potential of securing a brighter future for all. For now, we await the beautiful ones—who are not yet born!

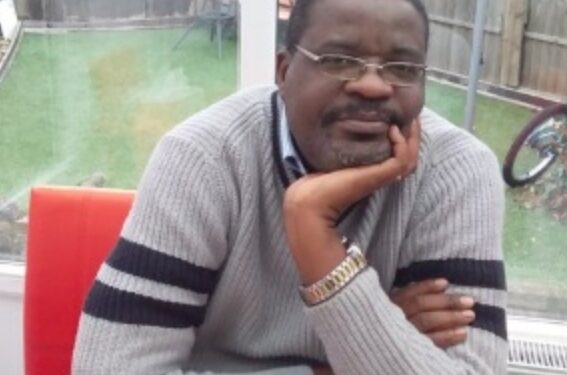

Abdul Mahmud is a human rights attorney in Abuja